Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the third most common hospital-acquired infection in Australia (Lydeamore et al. 2022).

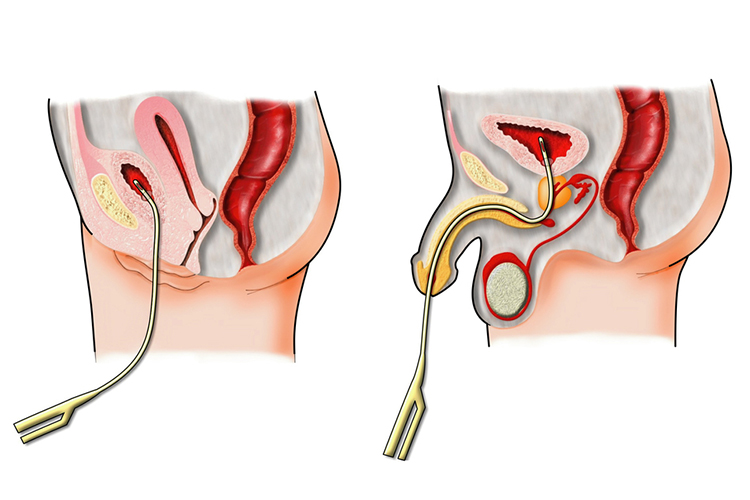

About 80% of hospital-acquired UTIs are associated with the use of an indwelling urinary catheter (IDC) (ACSQHC 2018). This is a significant number, considering that there is a 15 to 25% chance of a hospitalised patient needing a catheter inserted at some point during their stay (CDC 2015). These infections, due to their aetiology, are commonly referred to as catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI).

In addition to potentially developing an infection, a patient requiring an IDC may also experience other complications, such as urethral strictures, mechanical trauma and bladder irritation (Nickson 2020). CAUTI, along with other HAIs, have also been found to result in an increased length of stay in hospital for the patient and are associated with an increased risk of mortality (ACSQHC 2018).

This increased risk of mortality may be linked to the fact that CAUTI are one of the most common causes of secondary bloodstream infections (Werneburg 2022).

Risk Factors for Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections

The following factors increase the risk of CAUTI:

- Long duration of catheterisation

- Female sex

- Comorbidity (e.g. diabetes).

(ACSQHC 2018)

Symptoms of Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections

CAUTI can be difficult to recognise in hospitalised patients because symptoms may be similar to the patient’s original illness (Nall & Weatherspoon 2017).

Generally, CAUTI can be diagnosed by the presence of bacteriuria along with symptoms including:

- Malaise

- Foul-smelling urine

- Discoloured or cloudy urine

- Blood in urine

- Leakage of urine around the catheter

- Pain or discomfort in the lower abdomen or back

- Chills

- Fever

- Vomiting

- Pain when urinating

- Urinary urgency or frequency

- Altered mental state (in older adults).

(Gilbert et al. 2018; Nall & Weatherspoon 2017; Sabih & Leslie 2023)

Preventing Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections

The focus of managing CAUTI should be on prevention. If the risk of infection increases with the use of an IDC, then we can minimise catheter use on patients. When catheters are necessary, they should be removed as soon as possible.

By lowering the causative factor of the infections, we are decreasing the rate of infections occurring. It has been found that for each day a catheter remains in, the patient's risk of acquiring a CAUTI increases by 3 to 7% (Whitaker et al. 2023).

The increased risk of prolonged IDC use can be attributed to the development of a biofilm on the catheter. As with any device that has the potential to develop a biofilm, the longer the device stays in situ, the longer the biofilm will be in place and be a harbour for potential microorganism growth (Sabih & Leslie 2023).

Biofilm is a complex material and consists of many microorganisms growing on the surface of the object. In the case of a catheter, the biofilm will not only be present on the outside of the catheter but will also be present on the inside of the tubing. This biofilm formation will begin immediately after insertion of the catheter, hence the focus on removing the catheter as soon as it is no longer needed (Nicolle 2014).

An IDC should not be used on a patient for a prolonged period of time without the appropriate indications for use, or as a substitute for nursing care on a patient with incontinence. Generally, indwelling catheters should be used in the following situations:

- Urinary retention

- When there is a need for accurate measurements of urinary output

- To instil medications

- Perioperative use for specific surgical procedures

- Bladder irrigation to manage haematuria

- Management of fistula

- Preservation of skin integrity (e.g. to promote the healing of sacral or perineal wounds in patients who are incontinent)

- End-of-life care.

(ACI 2017; Queensland Health 2023)

Nursing Considerations

Prevention of CAUTI also relies on the provision of appropriate nursing care. This means ensuring the use of proper techniques for inserting the catheter and performing ongoing maintenance.

Only trained practitioners should be inserting IDCs, and this must be performed using aseptic technique and sterile equipment. The smallest catheter size appropriate for the patient should be chosen. It is also important to note that infection risks are similar with both latex and silicone-based catheters. After insertion of the IDC, it should be maintained as a closed drainage system, and if there is a disconnection, replacement of the items should occur (SA Health 2022; Werneburg 2022).

It is also important that nurses ensure that the catheter remains free from any kinks and that the collecting bag remains below the level of the bladder at all times to maintain unobstructed urine flow, which will also help to prevent infections (ACI 2017).

IDC management should also include ensuring the catheter is properly secured in order to prevent movement and urethral traction. The collection bag should be emptied regularly, with the nurse avoiding touching the draining spigot to the collecting container (SA Health 2022).

Note that the drainage bag of a patient with a CAUTI can act as a reservoir for organisms. These can then be transmitted to other patients through the hands of healthcare personnel. Outbreaks of infections that are associated with resistant gram-negative organisms that are attributable to bacteriuria in patients with catheters have been reported (Lo et al. 2014).

Maintaining perineal hygiene is also important when caring for a patient with an IDC (Queensland Health 2023).

The main consideration for IDC nursing care is based on the primary principle of treating CAUTI: prevention. If the IDC is not clinically indicated, we should not be inserting it, and if it’s no longer needed, it is time to remove it.

Topics

References

- Agency for Clinical Innovation 2017, Male Indwelling Urinary Catheterisation (IUC) - Adult, New South Wales Government, viewed 22 November 2023, https://aci.health.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/256133/ACI_Male_IUCv3.pdf

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2018, Healthcare-associated Infections, Australian Government, viewed 21 November 2023, https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/SAQ7730_HAC_Factsheet_HealthcareAssociatedInfections_LongV2.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015, Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infections, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, viewed 21 November 2023, https://www.cdc.gov/hai/ca_uti/uti.html

- Gilbert, B, Naidoo, TL & Redwig, F 2018, ‘Ins and Outs of Urinary Catheters’, Australian Journal of General Practice, vol. 47, no. 3, viewed 22 November 2023, https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/2018/march/ins-and-outs-of-urinary-catheters

- Lo, E et al. 2014, ‘Strategies to Prevent Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2014 update,’ Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, vol. 35, no. 5, viewed 22 November 2023, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/675718

- Lydeamore, MJ et al. 2022, ‘Burden of Five Healthcare Associated Infections in Australia’, Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, vol. 11, no. 69, viewed 21 November 2023, https://aricjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13756-022-01109-8

- Nall, R & Weatherspoon, D 2017, ‘Catheter Associated UTI (CAUTI)’, Healthline, 20 March, viewed 22 November 2023, https://www.healthline.com/health/catheter-associated-uti

- Nickson, C 2020, Urinary Catheter (IDC or Foley), Life in the Fast Lane, viewed 21 November 2023, https://litfl.com/urinary-catheter-idc-or-foley/

- Nicolle, LE 2014, ‘Catheter Associated Urinary Tract Infections’, Antimicrobial Resistance and Infection Control, vol. 3, no. 23, viewed 22 November 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4114799/

- Queensland Health 2023, Urinary Catheter Insertion or Change, Queensland Government, viewed 22 November 2023, https://www.health.qld.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0031/1243786/36.Urinary-catheter-insertion-or-change.pdf

- SA Health 2022, Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infection Prevention, Government of South Australia, viewed 22 November 2023, https://www.sahealth.sa.gov.au/wps/wcm/connect/public+content/sa+health+internet/clinical+resources/clinical+programs+and+practice+guidelines/infection+and+injury+management/healthcare+associated+infections/indwelling+medical+device+management/preventing+catheter-associated+urinary+tract+infection

- Sabih, A & Leslie, SW 2023, ‘Complicated Urinary Tract Infections’, StatPearls, viewed 22 November 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436013/

- Werneburg, GT 2022, ‘Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections: Current Challenges and Future Prospects’, Res Rep Urol., vol. 14, viewed 21 November 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8992741/

- Whitaker, A, Colgrove, G, Scheutzow, M, Ramic, M, Monaco, K & Hill Jr., JL 2023, ‘Decreasing Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infection (CAUTI) at a Community Academic Medical Center Using a Multidisciplinary Team Employing a Multi-Pronged Approach During the COVID-19 Pandemic’, Am J Infect Control., vol. 51, no. 3, viewed 22 November 2023, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9357278/

New

New