This article will discuss how to assess a deteriorating/critically ill patient using the ABCDE (airway, breathing, circulation, disability and exposure) systematic approach.

The ABCDE approach is intended for rapid assessment of a deteriorating/critically ill patient. It’s designed to provide initial management of life-threatening conditions in order of priority, using a structured method to keep the patient alive and to achieve the first steps to improvement rather than making a definitive diagnosis (Farrington 2025).

The ABCDE Assessment:

Airway (A)

The aim of the airway assessment is to establish the patency of the airway and assess the risk of deterioration in the patient’s ability to protect their airways.

A quick way to identify the patency of the patient's airway is as follows:

- If the patient can speak, this indicates that their airway is clear and patent.

- If the air entry is diminished and often noisy, this indicates a partial obstruction to the airway.

- If there are no breath sounds at the mouth or nose, this indicates a complete obstruction of the airway.

(Resuscitation Council UK 2024; Planas et al. 2023)

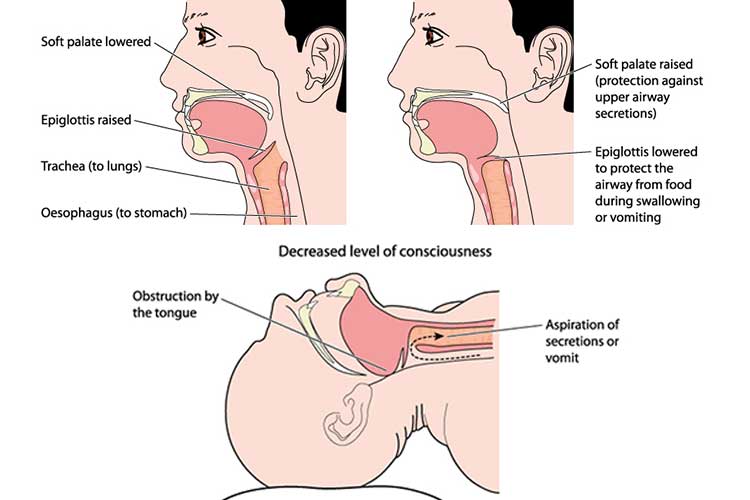

Causes of Airway Obstruction

Airway obstruction could be caused by:

- The patient’s tongue

- Foreign body

- Vomit, blood or secretions

- Swelling of soft tissue e.g. anaphylaxis

- Local mass effect (e.g. tumour)

- Laryngospasm

- Reduced consciousness e.g. head injury, stroke, overdose.

(AMBOSS 2024; Farrington 2025)

Assessing the Airway

- Observe the patient for signs of airway obstruction such as paradoxical chest and abdominal movements. This refers to a state whereby the chest and abdomen rise and fall alternatively and vigorously to attempt to overcome the obstruction.

- Look to identify whether skin colour is blue or mottled (cyanosis).

- Listen for signs of airway obstruction. Certain sounds will assist you in localising the level of the obstruction. For example, noises such as snoring, expiratory wheezing or gurgling may indicate a partially obstructed airway.

- Listen and feel for airway obstruction: If the breath sounds are quiet, then air entry should be confirmed by placing your face or hand in front of the patient’s mouth and nose to determine airflow, by observing the chest and abdomen for symmetrical chest expansion, or listening for breath sounds with a stethoscope.

(Resuscitation Council UK 2011, 2024; Farrington 2025)

Airway Obstruction Management

- According to the Resuscitation Council UK (2024), airway obstruction should be treated as a medical emergency. Expert help should be called immediately as untreated airway obstruction can rapidly lead to cardiac arrest, hypoxia, damage to the brain, heart or kidneys, and even death.

- Once airway obstruction has been identified, treat it appropriately. For example, suction if required, administer oxygen as appropriate and move the patient into a lateral position.

- If the patient is unconscious or has an altered conscious state, is not breathing normally or cannot maintain airway patency, use the head tilt/chin lift manoeuvre or jaw thrust to open their airway.

(Resuscitation Council UK 2024; AMBOSS 2024; Ernstmeyer & Christman 2021; Farrington 2025)

Breathing (B)

Breathing function should only be assessed and managed after the airway has been judged as adequate..

Assessment of breathing is designed to detect signs of respiratory distress or inadequate ventilation. The following steps can be used to assess breathing:

Assessing Breathing

- Look for general signs of respiratory distress, such as sweating, increased effort to breathe, abdominal breathing and central cyanosis.

- Count the patient’s respiratory rate: the normal respiratory rate in adults is between 12 and 20 breaths per minute. The respiratory rate should be measured by counting the number of breaths that a patient takes over one whole minute by observing the rise and fall of the chest. A high respiratory rate is a marker of illness or an early warning sign that the patient may be deteriorating.

- Assess the depth of each breath the patient takes, the rhythm of breathing and whether chest movement is equal on both sides.

- Measure the patient’s peripheral oxygen saturation using a pulse oximeter applied to the end of the patient’s finger. The Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand (2022) recommends a target oxygen saturation of between 92 and 96% for most critically ill adults, or 88 to 92% for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or other conditions associated with chronic respiratory failure.

- Blood gas analysis: This test provides a valuable respiratory assessment of the levels of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood and the blood PH. It provides more in-depth information about the effectiveness of respiratory function than pulse oximetry.

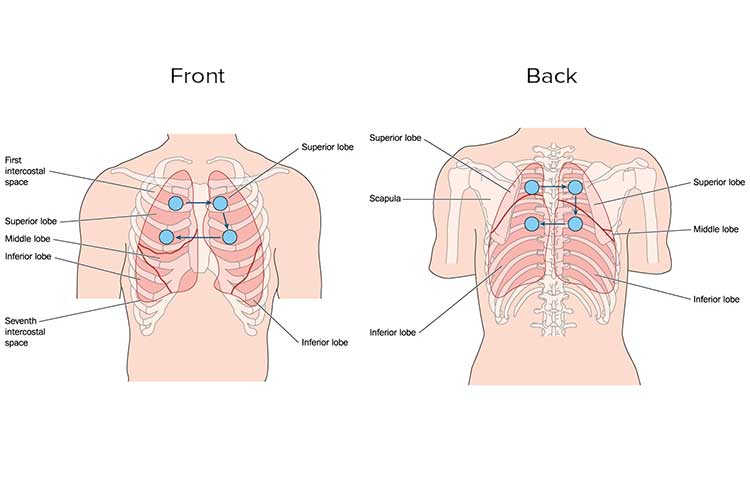

- Assess air entry using a stethoscope to confirm whether air is entering the lungs, whether both lungs have equal air entry and whether there are any additional abnormal breath sounds such as wheezing and crackles.

(Resuscitation Council UK 2023; Barnett et al. 2022; Farrington 2025)

Management

The treatment of specific respiratory disorders depends upon the cause. However, expert help should be called immediately in any case (Resuscitation Council UK 2024). If the patient’s breathing is compromised, position them appropriately (usually in an upright position) (Farrington 2025).

Circulation (C)

Assessment of circulation should be undertaken only once the patient’s airway and breathing have been assessed and appropriately treated.

Assessing the circulatory system aims to determine the effectiveness of cardiac output, (i.e. the volume of blood ejected from the heart each minute).

Causes of Poor Circulation

Possible causes include, but are not limited to:

- Shock (including distributive, cardiogenic, hypovolemic and obstructive shock)

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Heart failure

- Hypertension

- Coronary disease

- Congenital conditions

- Myocardial ischaemia and infarction

- Genetic conditions

- Structural abnormalities

- Emboli.

(King & Lowery 2023)

Assessing Circulation

- Blood pressure (BP) is an indication of the effectiveness of cardiac output. Measure the patient’s blood pressure as soon as possible; low blood pressure (relative to the patient's normal blood pressure) is often a late sign in a deteriorating patient and can be an adverse clinical sign.

- Gauge the patient’s peripheral skin temperature by feeling their hands to determine whether they are warm or cool.

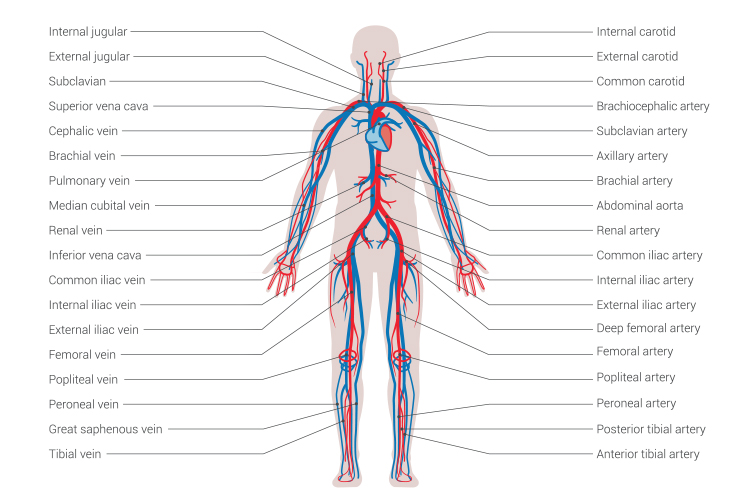

- Feel and measure the patient’s heart rate: assess the patient’s heart rate relative to their normal physiological condition. Heart rate is usually felt by palpating the pulse from an artery that lies near the surface of the skin, such as the radial artery in the wrist. The pulse should be felt for presence, rate, quality and regularity. If there are any abnormalities detected such as thread pulse, then a 12 lead electrocardiogram (ECG) should be undertaken.

- Capillary refill time (CRT): a simple measure of peripheral circulation. The patient’s hand should be at the level of their heart. Press the top of the patient’s finger for 5 seconds to blanch the skin, and then release. The normal value for CRT is usually < 2 seconds. A prolonged CRT could indicate poor peripheral perfusion.

- Look for other signs of poor cardiac output such as a decreased level of consciousness. If the patient has a urinary catheter, check for reduced urine output (urine output of < 0.5 mL kg/hr) and assess for any signs of external bleeding from wounds or drains.

(Resuscitation Council UK 2024; Hagedoorn et al. 2019; NHLBI 2022)

Management

The specific treatment for circulation problems depends on the cause. However, fluid replacement, restoration of tissue perfusion and haemorrhage control are usually necessary (Resuscitation Council UK 2024).

- Ensure the patient has one or more large gauge intravenous cannulas in situ so that emergency fluids and medicines can be administered more efficiently.

- Remember to continuously reassess the patient’s heart rate and blood pressure, with the goal of restoring them to the patient’s normal physiological state. If this is not known, aim for > 100 mmHg systolic.

- Seek help from more experienced practitioners.

(Resuscitation Council UK 2024)

Disability (D)

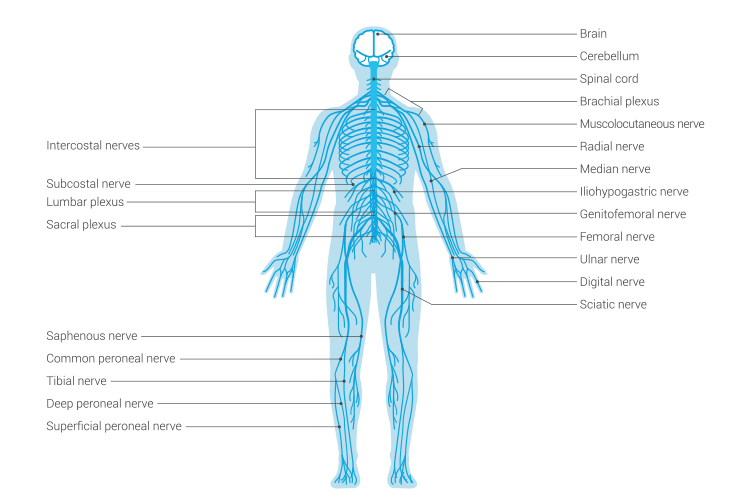

This assessment involves reviewing the patient’s neurological status, and should only be undertaken once A, B and C above have been optimised, as these parameters can all affect the patient’s neurological condition.

Assessing Neurological Function

- Level of consciousness: Conduct a rapid assessment of the patient’s level of consciousness using the AVPU system:

- Awake (A): Observe if the patient can open their eyes, takes interest and responds normally to their environment. This would be assessed as ‘awake’.

- Responding to voice (V): If the patient has their eyes closed and only opens them when spoken to, this would be assessed as ‘voice’.

- Responding to pain (P): If a patient doesn’t respond to voice, painful stimuli should be applied. If the patient responds to painful stimuli, then the level of consciousness is assessed as ‘responds to pain’. An example of a painful stimulus is the ‘trapezius squeeze’.

- Unresponsive (U): A patient not responding to pain is ‘unresponsive’.

(Romanelli & Farrell 2023)

- If you’re concerned about the patient’s level of consciousness, then use a more in-depth assessment such as the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) and seek further help.

- Pupil reaction: Examine the patient’s pupils for size, shape and reaction to light.

- Blood glucose levels: A blood glucose measurement should be taken to exclude hypoglycaemia using a rapid finger-prick bedside testing method. Follow local protocols for management of hypoglycaemia.

(Resuscitation Council UK 2024)

Management of Altered Consciousness Level

- The priority is to assess airway, breathing and circulation to exclude hypoxia and hypotension.

- Check the patient’s medicine chart for reversible medicine-induced causes of an altered level of consciousness, and remember to call for expert help.

- Unconscious patients whose airways are not protected should be nursed in the lateral position.

(Resuscitation Council UK 2024)

Exposure (E)

By the time the assessment reaches this stage (exposure), there should be a good understanding of the patient’s problems.

Assessing Exposure

- Conduct a thorough examination of the patient’s body for abnormalities, checking the skin for the presence of rashes, swelling, bleeding or any excessive losses from drains. Respect the patient’s dignity at all times and minimise heat loss.

- Look at the patient’s medical notes, medicine charts, observation charts and results from investigations for any additional evidence that can inform the assessment and ongoing plan of care for the patient.

- Remember to document all the assessments, treatments and responses to treatment in the patient’s clinical notes.

- Always seek help from more senior or experienced practitioners if the patient is continuing to deteriorate.

- Patient’s temperature: normal temperatures range from 36.5°C to 37.5°C. If a patient has a raised temperature, it is important to understand the reason for this, as the treatment will vary depending on the cause.

(Farrington 2025; Osilla et al. 2023)

Conclusion

The ABCDE approach is a robust clinical tool that enables healthcare professionals to determine the seriousness of a patient’s condition and prioritise clinical interventions.

Your facility’s policies and procedures should always be followed when responding to/managing a critically ill or deteriorating patient.

Test Your Knowledge

Question 1 of 3

Which one of the following is the greatest priority when assessing a deteriorating patient?

Topics

Further your knowledge

References

- AMBOSS 2024, Airway Management, AMBOSS, viewed 24 March 2025, https://www.amboss.com/us/knowledge/airway-management

- Barnett et al. 2022, ‘Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand Position Statement on Acute Oxygen Use in Adults: ‘Swimming Between the Flags’ ’, Respirology, vol. 27, no. 4, viewed 24 March 2025, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/resp.14218

- Ernstmeyer, K & Christman, E 2021, ‘Chapter 10 Respiratory Assessment’, in Nursing Skills, Chippewa Valley Technical College, Eau Claire, viewed 24 March 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK593192/

- Farrington, G 2025, ABCDE Assessment – OSCE Guide, Geeky Medics, viewed 24 March 2025, https://geekymedics.com/abcde-approach/

- Hagedoorn, NN, Zachariasse, JM & Moll, HA 2019, ‘Association Between Hypotension and Serious Illness in the Emergency Department: An Observational Study’, Arch Dis Child., vol. 105, no. 6, viewed 24 March 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7285787/

- King, J & Lowery, DR 2023, ‘Physiology, Cardiac Output’, StatPearls, viewed 24 March 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470455/

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2022, Arrhythmias: Diagnosis, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, viewed 24 March 2025, https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/arrhythmias/diagnosis

- Osilla, EV, Marsidi, JL, Shumway, KR & Sharma, S 2023, ‘Physiology, Temperature Regulation’, StatPearls, viewed 24 March 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507838/

- Planas, JH, Waseem, M & Sigmon, DF 2023, ‘Trauma Primary Survey’, StatPearls, viewed 24 March 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430800/

- Resuscitation Council UK 2011, Chapter 7 Airway Management and Ventilation, Resuscitation Council UK, viewed 24 March 2025, https://lms.resus.org.uk/modules/m65-non-technical-skills/resources/chapter_7.pdf

- Resuscitation Council UK 2024, The ABCDE Approach, Resuscitation Council UK, viewed 24 March 2025, https://www.resus.org.uk/library/abcde-approach

- Romanelli, D & Farrell, MW 2023, ‘AVPU Scale’, StatPearls, viewed 24 March 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538431/

New

New