The Importance of Research in L&D

Learning and Development (L&D) teams in healthcare settings, such as hospitals and aged care facilities, play a vital role in shaping the skills and knowledge of clinical and non-clinical staff. Whether it's through education programs for nurses, leadership training for administrators, or compliance training for support staff, the effectiveness of these initiatives has a direct impact on patient care, operational efficiency, and staff satisfaction.

Turning “We Think” into “We Know”

When healthcare organisations face budgetary pressures, education initiatives that are not viewed as directly impacting staff performance, improving patient care and outcomes, or reducing healthcare costs may face funding cuts more readily. However, initiatives with proven positive outcomes are more likely to be judged on their merits rather than assumptions made by individuals outside the L&D team. L&D teams can use research assumptions to support their initiatives, namely, that research processes are thorough and ethical, that researchers are experts, and that research findings are factual and data-driven. Research can essentially ‘rubber stamp’ an education initiative, shifting the discussion about its continuing existence from “We think this initiative improves outcomes” to “This initiative does improve outcomes.”

With research, you can provide evidence for how education and L&D initiatives impact clinical outcomes or operational efficiencies within hospitals or aged care organisations. This will thereby show the value of your work and improve your chances of securing ongoing funding and support.

Overcoming Common Barriers to Research in L&D

Understandably, L&D teams may face barriers to incorporating research into practice. They may be time-poor, managing already high workloads, making it difficult to engage in research. A lack of expertise and a perception of research as “hard” or exclusively done by “experts” are also legitimate mental barriers. Limited resources, particularly access to research support, data, research tools, and financial support, can further complicate undertaking research.

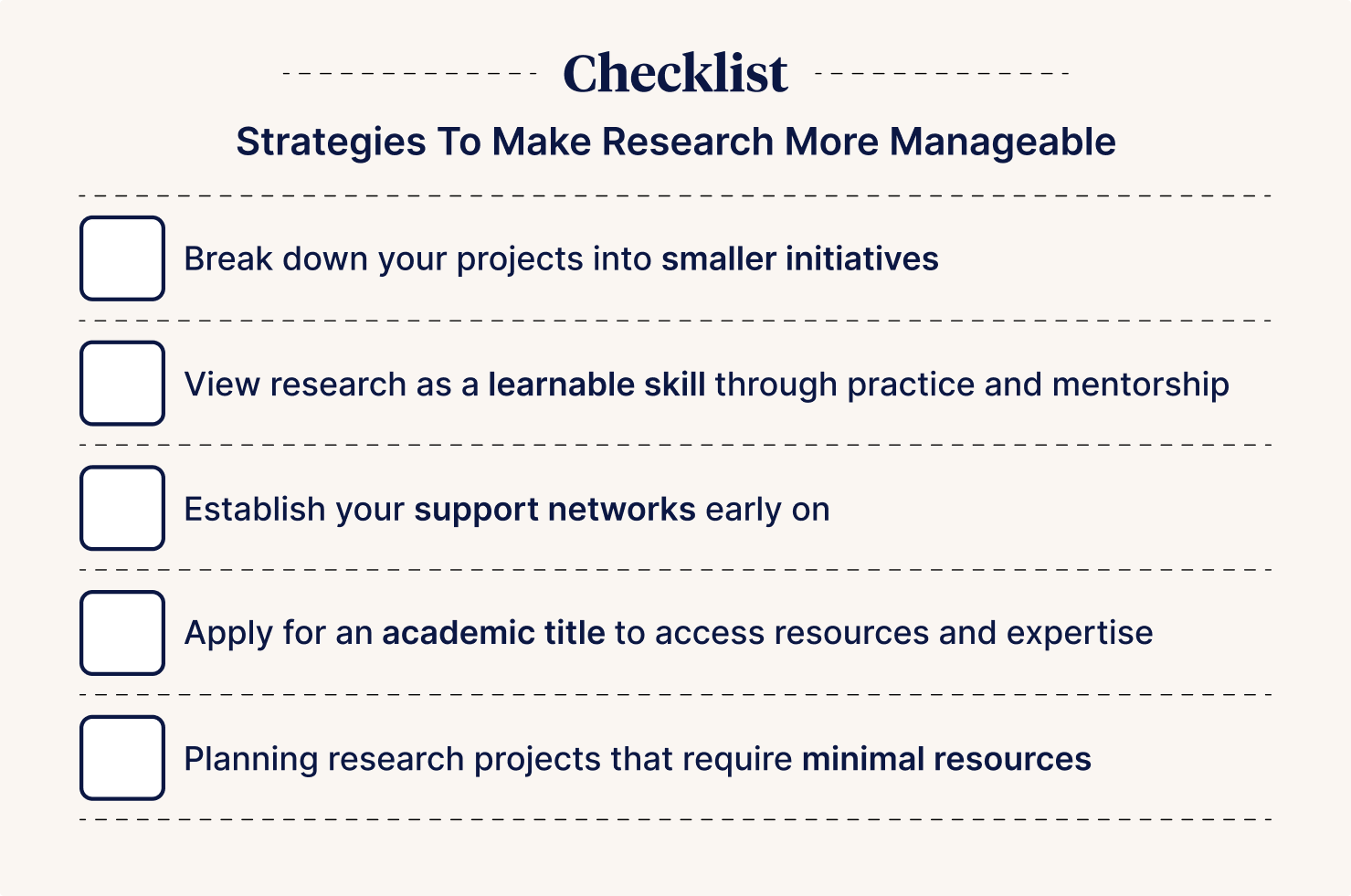

Making Research Manageable

To make research more achievable, consider these strategies:

- Break projects into smaller, manageable initiatives

- View research as a learnable skill through practice and mentorship

- Establish support networks early

- Apply for an academic title to access resources and expertise

- Plan research projects that require minimal resources e.g. qualitative research.

Qualitative research methods are inherently budget-friendly, as data collection often involves recording conversations or collecting surveys.

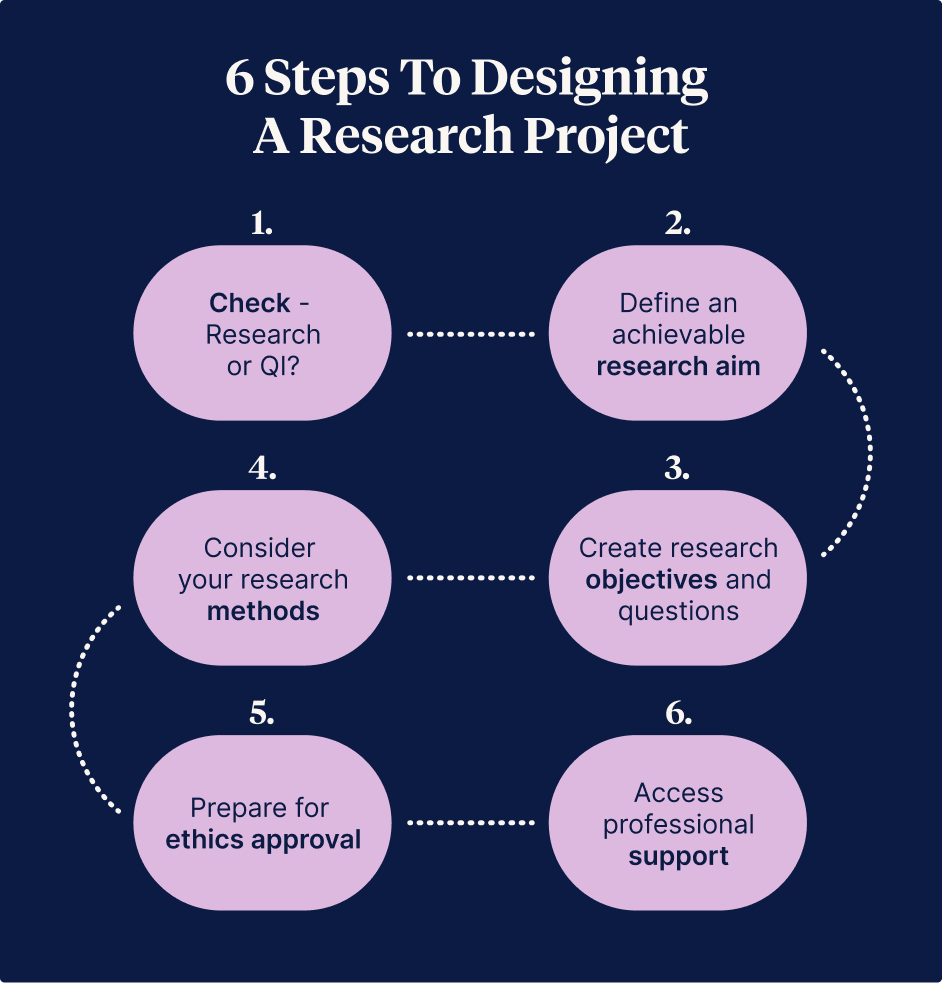

A Step-by-Step Guide to Designing a Research Project

A structured framework is invaluable; therefore, a brief step-by-step guide for designing a research project is provided below.

- Check - Research or QI?

- Define an achievable research aim

- Create research objectives and questions

- Consider your research methods

- Prepare for ethics approval

- Access professional support

Step 1 - Check: Research or QI?

In my experience, novice researchers, particularly healthcare workers, often confuse research with quality improvement activities. The distinction is critical because research often requires formal ethical approval, while quality improvement activities generally have fewer ethical requirements. Consider which of the following best describes your project idea:

- My project focuses on discovering new information and exploring the best ways to do things.

- My project focuses on evaluating how well current best practices are being carried out.

If your answer aligns with statement one, you are most likely planning research. Research seeks new information, while quality improvement ensures current processes align with established guidelines.

If your project is a quality improvement activity, seek guidance from your research office or local university on how to proceed and consider the advice provided by the National Health and Medical Research Council (2014).

Step 2 - Define an Achievable Research Aim

Now that you are reasonably confident you are conducting research, it is important to determine what you ultimately want to achieve. In my experience, your end goal often differs from the specific objectives of your research. It may simply be “to provide evidence supporting the continuation or existence of my initiative.”

To maintain an initiative, you should ideally provide data demonstrating important outcomes to your organisation.

For instance, if a hospital is focusing on reducing adverse events, the L&D team could conduct research to assess the effectiveness of clinical training programs on improving error reporting and reducing mistakes.

Similarly, if improving patient experience is a priority, research could evaluate the impact of customer service or communication training on patient satisfaction.

As you brainstorm, you may identify numerous potential sources of data points. However, you will unlikely be able to collect and analyse all of them. You need to ensure your project size is manageable, especially since you’ll likely be working on your research in addition to your regular duties. A project that investigates everything probably isn’t feasible.

Tip: Focus only on the most critical aspects and ensure alignment with organisational priorities.

From here, you can write your research aim*. A research aim is a simple statement summarising the overall purpose of your project. It is the type of sentence you can confidently state when someone asks, “What is your research project about?” For example, “This research explores how students learn from role models in clinical settings.”

* Consider reading the following guide for additional examples on research aims, objectives, and questions: https://gradcoach.com/research-aims-objectives-questions/.

Step 3 - Create Your Research Objective(s) and Question(s)

A research objective is a statement describing what your research aims to achieve. Essentially, objectives serve as a strategy to break your research into manageable parts.

For example, “To assess differences in interns’ patient-centred care approaches based on their role model exposure.” For novice researchers, having 1–3 objectives is sufficient. Once your objectives are written, you can reword them as research questions.

For example, the previous objective could become, “Does exposure to negative role models impact medical students’ provision of patient-centred care?” With your research aim, objectives, and questions clarified, you can now consider how to conduct your research.

| Research Aim | Research Objective | Research Questions |

|---|---|---|

| This research explores how students learn from role models in clinical settings. | To assess differences in interns’ patient-centred care approaches based on their role model exposure. | Does exposure to negative role models impact medical students’ provision of patient-centred care? |

Step 4 - Consider Your Methods

Your choice of research methods will depend on the questions you seek to answer. Over time, research methods have expanded into many options, which can feel overwhelming to novice researchers (and even experienced ones like the author).

A simple recommendation is to start with a basic overview of methods and identify which general approaches align with your research. From there, seek support to finalise your decision.

If your research involves mathematics or statistics, consult a statistician; if it requires financial analysis, speak with a health economist; or if it focuses on people’s experiences, consult a researcher with experience in qualitative methods.

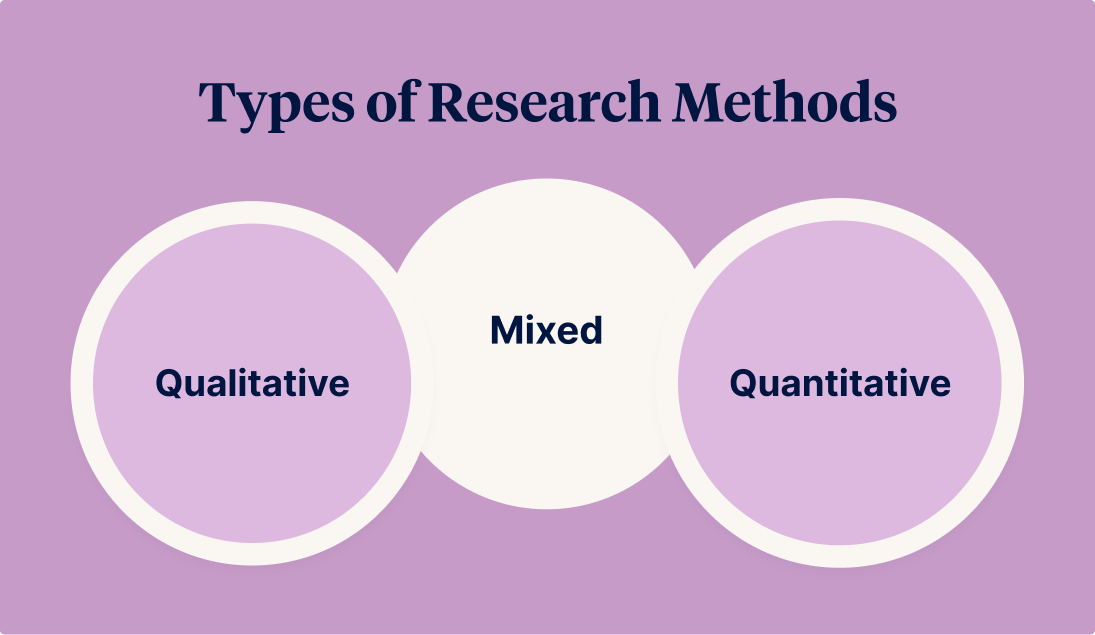

Types of Research Methods

Research methods fall into three broad categories: quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods (both quantitative and qualitative).

Below is a simplified guide for choosing the right category, followed by a more detailed exploration of each.

| Type | Key Question | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Methods | Do I need to quantify or statistically prove my findings?

|

|

| Qualitative Methods | Do my findings explore people’s experiences and perspectives?

· |

|

| Mixed Methods | Do I need aspects of both?

|

|

Quantitative Methods

Quantitative methods emphasise outcomes that can be measured numerically and statistically analysed under the right conditions to provide stronger evidence to support claims about your outcomes. A limitation of quantitative methods is that they can struggle to explain why things occur and tend to miss unexpected information.

For instance, “90% of respondents did not enjoy the session” tells you something is wrong but not what. Quantitative methods excel when:

- The boundaries of your problem are well understood but not well measured (e.g., identifying the most impactful barriers to workforce participation from a list of known barriers).

- Relationships must be quantified (e.g., determining which part of a training program most impacts practice).

- A causal relationship must be statistically investigated (e.g., does this training course improve medical practitioners’ understanding of anaesthetic risks?).

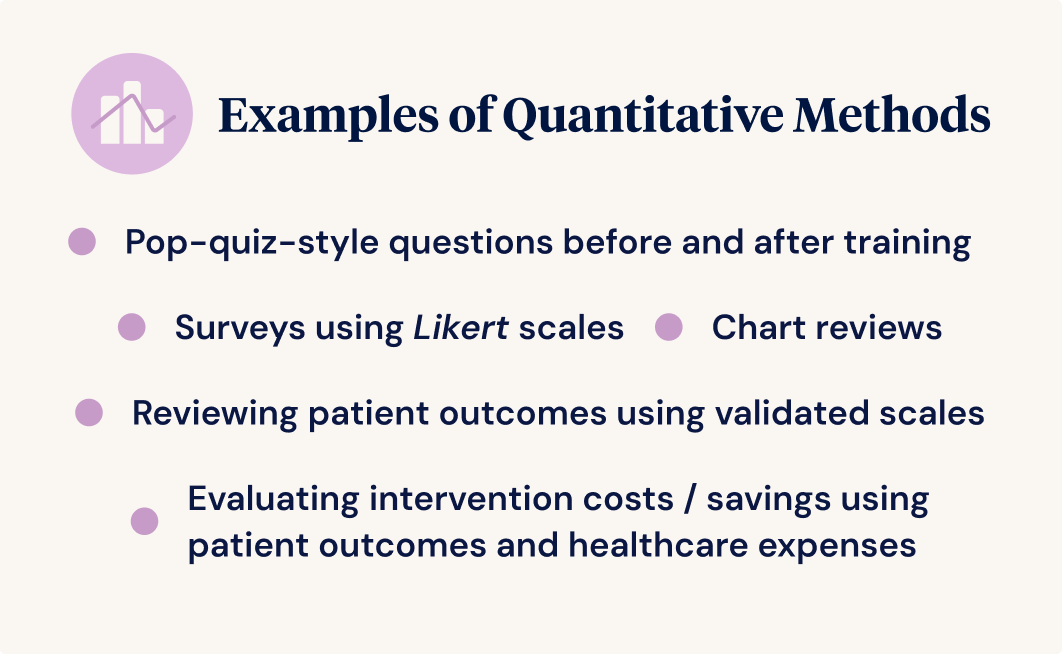

Examples of Quantitative Methods

- Surveys using Likert scales (e.g., “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”) administered pre-and post-training.

- Pop-quiz-style questions delivered before and after training.

- Reviewing patient outcomes using validated scales (e.g., a perceived exertion rating) to measure procedural changes' impact.

- Chart reviews to analyse links between risk factors and adverse events.

- Evaluating intervention costs/savings using patient outcomes and healthcare expenses.

For further reading, see Tavakol & Sanders (2014a).

Qualitative Methods

Qualitative methods illuminate participants’ experiences and beliefs, excelling at exploring issues that are not fully understood. These methods may come more naturally to novice researchers, as they rely on social interactions and typically require minimal mathematical or statistical knowledge. The trade-off for reduced mathematical and statistical knowledge is that qualitative methods require you to consider your paradigm (the lens through which you will view your findings) and methodology (your overall research process): concepts beyond this article's scope.

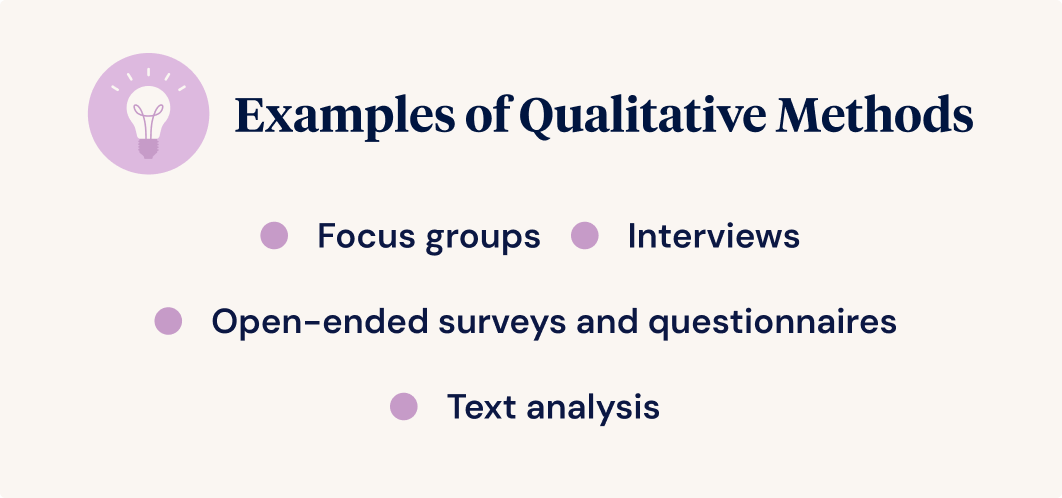

Examples of Qualitative Methods

- Focus groups: Enable in-depth feedback from multiple participants, with group interactions often eliciting insights not found in one-on-one settings.

- Interviews: These allow for detailed data collection and greater privacy, which is valuable for sensitive topics.

- Open-ended surveys/questionnaires: Reach a broader audience without scheduling constraints, though they may lack the depth of interviews or focus groups.

- Text analysis: Examines written documents (e.g., transcripts, journals) to uncover patterns in language use, behaviours, and social dynamics.

For further reading, see Tavakol & Sandars (2014b).

Mixed-Methods

Mixed methods combine aspects of both qualitative and quantitative methods. For instance, participants may complete a satisfaction survey (quantitative) and participate in a focus group discussion to explore their experiences further.

Mixed-methods approaches are beneficial because they do not limit one to choosing only quantitative or qualitative approaches. However, to successfully use a mixed-methods approach, one must understand mathematics, statistics, and a qualitative paradigm, methodology, and methods.

For further reading, see Fetters & Freshwater (2015) and Hesse-Biber & Johnson (2015).

Selecting the Right Research Method for Different Outcomes

When designing a research project, the choice of method depends on the type of outcome being assessed. The table below provides examples of how qualitative and quantitative research methods can be applied to different healthcare education and practice areas, based on the outcome you are trying to assess.

Research Methods by Outcome Type

| Outcome to be assessed | Example Methods |

|---|---|

| Patient/Resident Experience

|

Qualitative

Surveys or interviews with patients/residents and their families can capture feedback on their experience. |

| Quantitative

L&D programs focused on communication or empathy training can be assessed by using surveys to look at changes in practitioner/patient satisfaction scores before and after training. |

|

| Clinical Outcomes | Qualitative

Healthcare workers in general practice are asked to keep a daily journal documenting their infection control behaviours. Text analysis of the journals (e.g., word frequency analysis) is used to identify barriers and enablers to, and sentiments towards, infection control. |

| Quantitative

Clinical outcomes, such as infection rates or patient recovery times, can be linked to specific education initiatives, such as infection control training. The impact of L&D programs on these outcomes can be assessed through pre- and post-training data comparison using staff surveys and by comparing infection rates from pre- and post-training time periods. |

|

| Adverse Event Rates

|

Qualitative

Focus groups, interviews, and open-ended surveys may assist in understanding why particular adverse events are occurring at a greater-than-expected prevalence. |

| Quantitative

Research can track changes in the frequency and severity of adverse events (e.g., falls, medication errors) before and after education programs on safety practices. |

|

| Healthcare Costs/Savings | Qualitative

Physiotherapists participate in a focus group exploring what an ‘ideal’ training program for improving outpatient physiotherapy compliance would include. The group then completes a discrete choice experiment, discussing and selecting their most preferred training program components, simulating the effectiveness of limited financial resources. |

| Quantitative

Cost-benefit analysis can help demonstrate the financial impact of training programs. For example, training costs for improving outpatient compliance with physiotherapy could be compared to the change in readmission rates and costs over a three-month period. |

Step 5 - Preparing for Ethics

Before research can commence, ethical approval must be sought from a Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC). Depending on your employment, affiliations, and project population, an HREC may be accessed through a Hospital and Health Service, Private Hospital, or University, among other institutions. If you’re unsure which HRECs operate in your area, you may wish to consult the List of Human Research Ethics Committees registered with the National Health and Medical Research Council (n.d.). Many employers provide document templates to help support clinicians through ethics processes.

HRECs exist to ensure that research is conducted ethically and that historical wrongs, such as those in the cases of Henrietta Lacks and origins of HeLa cells, and the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, are not repeated (“Henrietta Lacks,” 2020; McVean, 2019). Despite the noble aims of HRECs, it is important to acknowledge that you may encounter individuals with negative experiences with these committees (Xu et al., 2020). If this happens, don’t be discouraged—simply focus on ensuring attention to detail in your ethics application, engage positively and graciously with your HREC, and be patient. Many guides to the ethics process are available in the literature to assist you (Ivers et al., 2023).

Step 6 - Access Professional Support

It is advisable to consider partnering with a researcher to gain additional support. Obtaining an academic title from a university, which provides access to university resources and support services, may enhance the availability of further specialist assistance (e.g., research librarians, statisticians, health economists).

Education on research methods and ethics can be accessed through organisations such as Ausmed, Universities, Health Translation Queensland, Darling Downs Health Innovation and Research Collaborative, Rural Research Collaborative Learning Network, and the Lowitja Institute, just to name a few.

Hypothetical Case Studies

Two theoretical case studies are provided here to demonstrate how research can be embedded into the work of L&D teams to provide evidence to support their educational initiatives.

Case Study 1: Reducing Medication Errors Through Education

A Melbourne hospital implemented a training program for nurses on medication safety. The L&D team conducted pre- and post-assessment surveys to measure knowledge, confidence, and skills before and after the course. They also tracked medication error reports over a six-month period.

Following the training, the hospital observed a 15% reduction in medication errors, and staff reported increased confidence in their medication administration practices. The L&D team used this data to secure additional funding to expand their medication safety training programs.

Case Study 2: Improving Patient Satisfaction through Communication Training

An aged care facility introduced a communication skills training program for staff to improve resident interactions. Pre- and post-training surveys were conducted with both staff and residents. Additionally, residents participated in focus groups to explore how staff communication had changed since the training was introduced.

The results showed a notable improvement in staff communication and a 10% increase in resident satisfaction scores. Thematic analysis of focus group transcripts revealed that residents were more likely to converse with staff who provided visual cues about their hobbies (e.g., a soccer ball sticker on their nametag).

The qualitative findings were used to encourage all healthcare workers in the facility to personalise their appearance in the workplace. The quantitative findings demonstrated the program's success, becoming a benchmark for implementing similar initiatives at other aged care facilities.

Embracing a Research Mindset

Incorporating research into L&D practices is not only feasible but essential to demonstrate the value of education and training initiatives in healthcare organisations. By starting small, choosing the right methods, and aligning research efforts with organisational priorities, L&D teams can provide robust evidence showing their work directly contributes to better clinical outcomes, improves patients’ experiences, and enhances operational efficiencies.

Healthcare educators should view research as an ongoing process, not a one-time task. By adopting a research mindset, L&D teams can continually refine their programs and demonstrate that investment in education leads to measurable improvements in care and performance. Now is the time for L&D teams to embrace research as an integral part of their practice—ensuring that they not only meet the challenges of budgetary constraints but also project their work's real, lasting impact.

References

- National Health and Medical Research Council. (2014). Ethical Considerations in Quality Assurance and Evaluation Activities. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/about-us/resources/ethical-considerations-quality-assurance-and-evaluation-activities.

- National Health and Medical Research Council. List of Human Research Ethics Committees

registered with NHMRC. Retrieved December 05, 2024, from https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/sites/

default/files/documents/attachments/Committee/HREC-Human-Research-Ethics-Committees-registered-with-NHMRC-LIST.pdf - Hesse-Biber, S. N., & Johnson, R. B. (Eds.). (2015). The Oxford handbook of multimethod and mixed methods research inquiry. Oxford University Press.

- Fetters, M. D., & Freshwater, D. (2015). Publishing a methodological mixed methods research article. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 9(3), 203-213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815594687

- Tavakol, M., & Sandars, J. (2014a). Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE Guide No 90: Part I. Medical Teacher, 36(9), 746–756. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.915298

- Tavakol, M., & Sandars, J. (2014b). Quantitative and qualitative methods in medical education research: AMEE Guide No 90: Part II. Medical Teacher, 36(10), 838–848. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2014.915297

- Henrietta Lacks: science must right a historical wrong. Nature. 2020 Sep;585(7823):7. DOI: 10.1038/d41586-020-02494-z. PMID: 32873976.

- McVean, E. (2019). 40 Years of Human Experimentation in America: The Tuskegee Study. McGill University. https://www.mcgill.ca/oss/article/history/40-years-human-experimentation-america-tuskegee-study

- Xu, A., Baysari, M. T., Stocker, S. L., Leow, L. J., Day, R. O., & Carland, J. E. (2020). Researchers’ views on, and experiences with, the requirement to obtain informed consent in research involving human participants: a qualitative study. BMC Medical Ethics, 21, 1-11.

- Ivers, R., Vuong, K., Rhee, J., & Williams, K. (2023). Demystifying human research ethics committee applications. Australian journal of general practice, 52(10), 721-727. https://doi.org/10.31128/AJGP-02-23-6733

Author

Dr WIlliam MacAskill

Dr. William MacAskill is a Post-Doctoral Research Fellow at Rural Medical Education Australia, Griffith University and the University of Queensland. With a strong foundation in education and science, William transitioned from teaching high school mathematics and science to undertaking health research. His academic qualifications include degrees in Education, Applied Science (Physics), and a PhD in Exercise Physiology.

William's research focuses on Medical Education, Health Workforce, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health, and Reflective Learning. He supervises various student-led initiatives, including multi-site clinical audits, primary research projects, and systematic reviews. An enthusiastic educator, he delivers research training to healthcare professionals through the Darling Downs Health Innovation and Research Collaborative (DDHIRC).

In 2023, William received a Research Award from the Australia and New Zealand Association for Health Professional Educators for his contributions to reflective learning. He is committed to producing research and training materials that are accessible, well-written and easily understood. For more details on William’s recent publications, visit his ORCID profile.