Understanding Burnout in Healthcare

The World Health Organisation (2019) defines burnout as a syndrome conceptualised by chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. The Healthcare Professionals Survey found that burnout rates remained alarmingly high from 2020 to 2022 (80% in 2020, 86% in 2021, and 84% in 2022).

Burnout negatively affects the emotional and physical wellbeing of healthcare workers, impacting their performance, the departments they work in, and the overall healthcare system. It increases the risk of medical errors, jeopardises patient safety, and contributes significantly to staff resignations—many leaving the profession entirely. With an ever-growing population dependent on healthy, engaged healthcare professionals, preventing burnout is not just a priority but essential.

A passionate undergraduate said to me this week:

"Nurses are special because most of them will tell you that they got into the profession because they care so much. That’s great, but it also makes them a really vulnerable population."

Ultra-caring nurses form the backbone of this field, yet these same individuals often burn out and leave.

Burnout is Not Just an Employee's Responsibility

Too often, management frames burnout prevention as an individual responsibility rather than an organisational priority. Yes, healthcare workers need to practice self-care, but research clearly shows that workplace culture, leadership, and management structures play the most significant role in staff wellbeing. A cohesive, supportive, and healthy workplace culture reduces burnout and enhances talent retention. I have worked in both toxic and healthy workplaces, and there is no doubt that leadership makes all the difference.

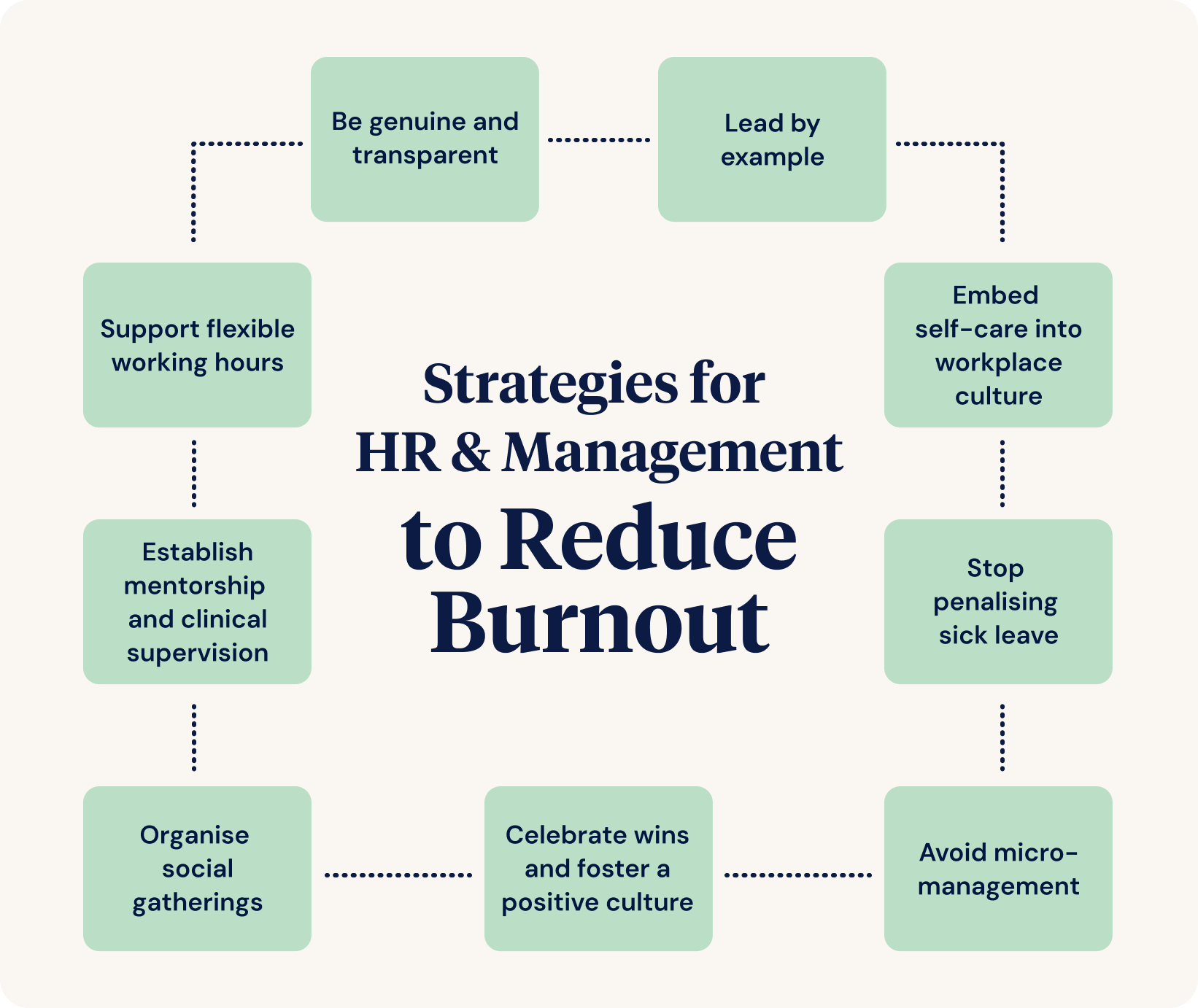

Strategies for HR and Management to Reduce Burnout

Here are strategies for HR and management to reduce burnout and retain valuable staff.

- Establish mentorship and clinical supervision

- Support flexible working hours

- Lead by example

- Embed self-care into workplace culture

- Stop penalising sick leave

- Be genuine and transparent

- Avoid micromanagement

- Celebrate strengths and foster a positive culture

- Organise social gatherings

1. Establish Mentorship and Clinical Supervision

As a mental health nurse, when I say ‘clinical supervision,’ many people think of performance management or professional learning pathways. Clinical supervision does not involve a manager. It’s essentially professional mentorship.

Clinical supervision is mandatory in the public sector in mental health due to its proven benefits in reducing burnout and fostering professional growth. However, clinical supervision was rarely mentioned when I worked in critical care, palliative care, and emergency care. All healthcare workers can benefit from structured mentorship and supervision.

- One-on-One Supervision - Monthly meetings in a neutral space (e.g., a café or courtyard) provide a confidential setting to discuss challenges.

- Group Supervision - This offers peer connection and support. Incorporating sensory tools (e.g., colouring books and fidget widgets) can help ease stress.

Regular supervision builds resilience, reduces stress, and strengthens staff retention. It should not be optional.

2. Support Flexible Working Hours

Having worked in different states across Australia, I have seen vast differences in workplace culture. In the ACT, workplaces actively supported part-time requests and hybrid roles. In other states, inflexible work arrangements led to early resignations.

If an employee has been asking to reduce from full-time to 0.8 FTE for years but is continuously denied, they will resign. Simple. While not every request can be met, when flexibility is possible, it should be supported.

3. Lead by Example

"Do as I say, not as I do" is an outdated leadership approach.

If managers stay back late and eat lunch at their desks, employees will feel pressured to do the same. Sustained poor self-care leads to burnout. A leader’s actions must match their words when encouraging staff wellbeing.

4. Embed Self-Care into Workplace Culture

We don’t need to meditate all day at work to look after ourselves and each other. Healthcare is fast-paced and demanding, but that doesn’t mean self-care can’t be integrated into the workday. Self-care isn’t just about meditation and mindfulness. It’s about small, meaningful moments. I’ve learned that even in the busiest and most chaotic workplaces, there are great self-care activities you can do together.

For example:

- Encourage lunch breaks - when someone hasn’t taken one, prompt them to step away.

- Start staff meetings with a positive reflection or a simple check-in.

- Small, fun activities can boost morale. One day, we found a leftover birthday balloon and spent five minutes keeping it off the ground. Everyone laughed, exercised, and felt a moment of joy.

With this in mind, suggestions for self-care for your staff must be genuine. Using the words ‘self-care’ can be a buzzword unless they come from an authentic place. If you do not show care for your staff in all the other moments in the day, then suggesting self-care activities just becomes an ugly mask.

5. Stop Penalising Sick Leave

Once, as an employee at a hospital, I was the 75th person that month to get norovirus. I called the shift manager, and she sighed and then said, ‘Not you too!, Okay, I’ll mark you down as sick.’ Later, she said ‘I hope you feel better soon’.

In a different workplace, when my grandad was dying during COVID, I took carer's leave to drive interstate to my hometown and support his care. I became so run-down and stressed that I actually lost my voice. I felt pressured to drive 666 km back the next day, as I had originally planned, to return to work—because we always seemed to be short-staffed, and my manager intimidated me.

I voiced this to my GP, and he said, ‘You cannot drive tomorrow; you need to rest.’ When I called my manager and painfully (literally) squeaked the words out about me needing more leave, she also sighed and then said, ‘Okay, I’ll mark you as sick.’

That’s all she said.

Healthcare workers (when they are not burnt out) are passionate about their job, so much so that they tend to put others before themselves. If someone is taking a sick day for whatever reason, support them. Maybe they do have gastro. Or maybe they have told you they have gastro because they need a mental health day because work has been super tough lately, and they are not coping.

It’s fair enough that as a manager, you feel stressed when people call in sick, but it's also inevitable. Wait to at least hang up the phone with the worker who has called in sick before you start projecting your stress onto them. Making workers feel bad for taking sick leave will definitely not have them coming back to work sooner.

In leadership roles, when I saw someone emotionally or physically fatigued, I would encourage them to have a day off. Sometimes, even just saying this to someone can be enough for them to at least feel cared for. Maybe they will take the day off to recover. Or maybe they will go home, have a bath and an early night and feel reassured that their boss cares about them.

6. Be Genuine and Transparent

Genuine, transparent leadership earns trust and reduces resentment. One of my worst managers told me she was trained never to apologise, as it admitted fault. Unsurprisingly, this mentality poisoned her leadership style.

In contrast, my best manager was honest and direct. When we had to complete another pointless litigious document, he acknowledged:

"I know this form doesn’t add to clinical care, but our funding depends on it. I know you're already drowning in paperwork, and I’m sorry to ask this, but we have to do it."

If you are asking a worker to do something that is going to be difficult for them, explain to them why you are asking them to do it while acknowledging their feelings and the system's shortcomings.

As a manager, you won’t necessarily have any control over the system's shortfalls, and you’ll have the added pressure from above (KPIs, funding, auditing) and then the pressure from your staff (feeling tired, overwhelmed, and stressed).

There is always a middle ground, but sometimes we have to dig deep to find it. I believe you can be both considerate and caring while still calling a spade a spade.

7. Avoid Micromanagement

Is this tactic taught in management school? Whoever taught it, please provide a course for people to unlearn it! Micromanaging is ineffective unless your goal is to feel powerful while making your workers feel disempowered. I’ve had managers who micromanaged, and it was painful - not just to experience, but to witness. Their strengths were buried beneath compensatory armour, stifling their leadership potential.

Micromanagers often:

- Have an unacknowledged inferiority complex (as many of us do to some extent).

- Struggle to delegate tasks, taking on too much themselves.

- Neglect their own self-care, creating a ripple effect of stress in the workplace.

- Create unhappy workers who mirror the same behaviours, fueling burnout.

If someone is underperforming, first ask:

- Do they need more training?

- Do they need more support?

When a staff member cares about their job but struggles, it’s often due to lack of support, not lack of effort.

Micromanaging destroys trust and confidence. Instead:

- Give staff autonomy. Trust them to do their jobs.

- Provide the right training and support before assuming incompetence.

- Step in only when necessary, rather than overseeing every small task.

Performance management might be needed if someone has had the necessary training and still isn’t meeting expectations. But hovering over everyone to catch a few bad apples only punishes the entire team.

I understand the challenge as someone who has had to actively work on letting go of control. When you care deeply, it’s hard to trust the process. But when workers are truly given the chance to do their jobs, they will be happier, and you will naturally identify who needs additional support.

8. Celebrate Strengths and Foster a Positive Culture

During COVID-19, I was asked to step into a leadership role. Feeling uncertain, I asked my mum (a brilliant teacher) for advice. She said:

"Let people do their work. Offer to help wherever you can. Remind them you’re there for them. Continuously acknowledge what they do well."

The antidote to micromanagement is keeping things strength-based.

Simple? Yes. Effective? Absolutely.

9. Organise Social Gatherings

We often spend more time with colleagues than family. So let’s be honest, hanging out with your colleagues all the time out of work might be a bit much, even if you are good mates. Healthy workplaces foster social connection without pressure.

One of my best workplaces had a standing Friday drinks invitation. There was no pressure or expectations, which created a safe, level playing field between staff and management and helped build relationships outside the stress of work.

The Role of Leadership in Retaining Talent

Great leadership is about balance, trust, and genuine care. I have been fortunate to work under exceptional managers who led with integrity, care, and respect. Ten years later, many of my colleagues from those workplaces are still there.

Burnout is preventable, but only if we build workplaces prioritising staff wellbeing. The best healthcare workers stay in the profession long enough to make a lasting impact, and it’s up to leadership to create an environment that enables them to do so.

References and Useful Resources

- Burnout Prevention for Healthcare Providers (2022) - CheckUP

- Burnout Recognised as an Occupational Phenomenon (n.d.) - GPMHSC

- Burnout Among Healthcare Workers: Impact and Prevention Strategies (n.d.) - National Library of Medicine

- Symptoms of Burnout and Workplace Stress (n.d.) - National Library of Medicine

- ICD-10 Classification: Depressive Episodes (F32) (2019) - World Health Organization

- ICD-10 Classification: Adjustment Disorders (F43.1) (2019) - World Health Organization

- Burnout Among Healthcare Workers and Patient Safety Risks (n.d.) - National Library of Medicine

Author

Rasa Kabaila

Rasa Kabaila is a Nurse Practitioner specialising in mental health and the founder of Broadleaf HNP Services. Her approach is innovative, holistic, individualised, and evidence-based, with a strong focus on recovery-oriented care. Deeply empathetic and passionate about helping others, Rasa began her healthcare career as a personal care worker at just sixteen.

She has successfully implemented research-backed clinical therapies for optimising the treatment of anxiety and depression, including pet therapy. Beyond her clinical work, Rasa has volunteered on nursing expeditions overseas and completed Ashtanga Yoga training in Mysore, India.

Rasa is also a Conjoint Lecturer with UNSW Rural Medical School and has been an academic tutor for undergraduate nurses and paramedics at the Australian Catholic University and the University of Canberra.

Her first book, Put Some Concrete in Your Breakfast: Tales from Contemporary Nursing, was published by Springer Nature in March 2023 and has since been read by over 17,000 readers. It has also been widely promoted across journals, magazines, and news channels.

For more about Rasa’s work, visit her practice website at Broadleaf HNP Services or explore her book, Put Some Concrete in Your Breakfast: Tales from Contemporary Nursing, featured on ABC News, available on Amazon and Goodreads.