Why Building Resilience Matters = Building Capability

Our healthcare workforce is dealing with immense pressures, compounded by limited time, stretched resources, and the constant expectation to provide uninterrupted high-quality care. Building workforce capability is about more than just meeting regulatory demands, ticking boxes, or completing mandatory training. It’s about equipping healthcare workers with the skills, confidence, and support they need to thrive in their roles, especially in the early years when they are most vulnerable.

Resilience plays a crucial part in this. But what does it actually mean to be resilient? More importantly, how do we teach resilience in a way that doesn’t just ask healthcare workers to “toughen up” or “push through” but instead fosters genuine, sustainable growth?

This piece explores what resilience looks like in healthcare, the misconceptions surrounding it, and the practical ways organisations and leaders can help build it without leaving the workforce, especially early career clinicians, to figure it out independently.

Redefining Resilience: More Than Just ‘Bouncing Back’

When trying to find a source that outlined resilience in the way that I understand it, as a human and also through a mental health lens, I just can’t find anything that I feel meets the mark. The Oxford Dictionary defines resilience as ‘the capacity to withstand or to recover quickly from difficulties; toughness’.

Resilience does mean ‘bouncing back’. I’m not a fan of the listed definitions of the word because they don’t imply how a person bounces back. To be resilient means that you have experienced a tough event and have managed to find a way through it.

But how do people find a way through it?

I’ve had a lot of non-health professionals in my life immediately assume that health professionals have found a way to become ‘desensitised’ to what they experience at work to survive in their jobs. I dislike this idea because it implies that health professionals have taught themselves to become dead on the inside to be able to cope.

This image is not one of resilience; it's one of burnout.

As health professionals, we can’t fall apart at every moment when something challenging happens, but we will also feel emotionally affected by our work when we care about it. It makes for a tricky space.

The Misconception of Resilience

When I was marking assignments for first and second-year nurses and paramedics on the topic of ‘resilience,’ it became clear to me that early career health workers know they are expected to be resilient. Still, they are unsure how to achieve such a state after experiencing adversity. I kept seeing this same example in assignments on the topic.

In many of the submissions, an example came up about a nurse who bore witness to the sudden death of a patient to who they were close, and then the nurse didn’t show any emotion; they told themselves to get over it, they reminded themselves that they are a professional and they were therefore resilient.

I commented on these papers, asking,

‘How realistic is it that a nurse close to a patient would be unaffected by it?’

‘If someone is emotionally affected by something, does that mean they are not resilient?’

Resilience Isn’t a Destination - It’s a Process

Admittedly, I don’t think I was ever taught about resilience as I headed into the health workforce. I understand it more now, but I wish I could have been supported with it when I first started off as a health care worker, arguably when I was most vulnerable: bright-eyed, bushy-tailed, with a bleeding heart but with no real sense of the adversity I would face in my role or how to manage it.

The term ‘resilient’ can sound slightly like some sort of Nirvana or enlightenment, and when you get there, you stay there. I don’t think that’s true. As humans and health professionals, we will continue to encounter different kinds of adversity in our professional and personal lives that may be incredibly painful and messy.

Resilience is in the process: how we make it to the other side repeatedly without dismissing the pain, suffering and confusion we experience with adversity. Many mental health literature, such as Very Well Mind (2024), will argue that each person is resilient; it’s not a characteristic that some people have and some don’t.

So why do some people appear to be more resilient than others? Is it Nature or Nurture?

The University of Michigan (2022) argues that it’s both. However, we also know that resilience can gain momentum with the right support systems at an organisational level (Human Focus, 2023).

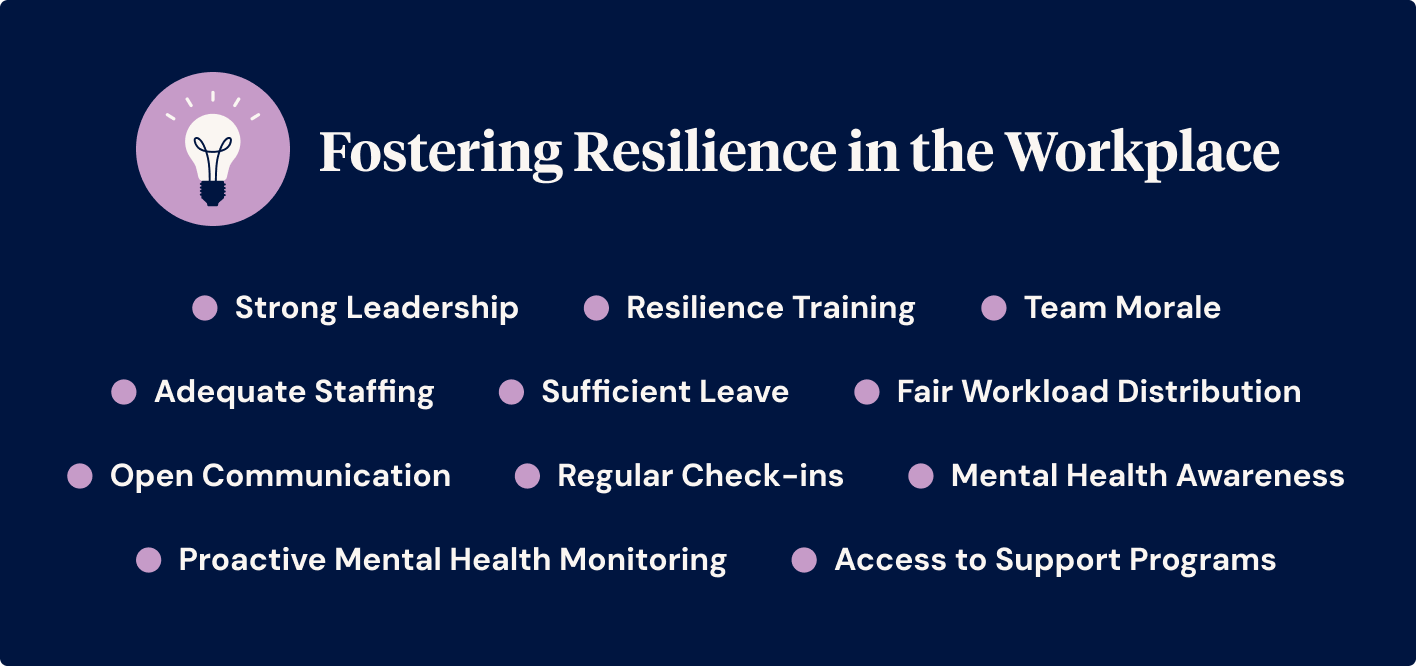

Fostering Resilience in the Workplace

Human Focus, 2023 goes on to list 11 points of how resilience can be fostered in the workplace.

- Ensuring that staff levels are adequate

- Focusing on building team morale

- Providing clear leadership

- Encouraging mental health awareness in the workplace

- Distributing workloads fairly

- Making sure employees are allowed sufficient leave when requested

- Creating open and confidential communication channels

- Arranging regular meetings with staff to discuss issues

- Providing mental health support programs

- Monitoring the mental health of employees

- Providing access to mental health resilience training

However, as a clinician and a researcher, I always think, ‘That’s great in theory, but what does this look like?’. So, I’ll break each of these down and think about how we can implement them in the workplace.

Adequate Staffing

When I asked Santa one Christmas for adequate staffing in the workplace, he laughed and gave me a candy cane. Having sufficient staffing levels in health care is key, but I’m not sure how realistic it is to show that we don’t even have enough nurses (for example) trained to meet service demands. This issue goes beyond management; it's a Government issue.

As a clinician, I know that it counts as a team approach to validating understaffing and advocating through the appropriate channels for more staff. When I worked in a medical ward, we had a nurse who was also a union representative. The union gave her guidance to put in a risk management report every time we were short on staff and fax the minister for health informing them of this!

Our Clinical Nurse Consultant (CNC) supported this and acknowledged our team when we were short-staffed. She could admit what was realistic for us to achieve in our shifts when we were short-staffed, taught us how to triage tasks, and encouraged us to triage our workload.

When I was a new graduate nurse, a clinical facilitator encouraged me to write down all the things I’d hoped to do for my patients in one day ‘my wish list’ - and also to know that this probably wouldn’t happen.

Then, she asked me to rewrite the list, which was colour-coded from green to red.

- Green tasks - Must be done during a shift - cannot be handed over.

- Yellow tasks - Attend to (if I have time) after completing the green tasks.

- Red tasks - Last tasks to be completed - only if the yellow tasks were completed. Can be handed over.

In addition, both my CNC and my clinical facilitator continuously acknowledged how hard we were working. All of these approaches combined supported me in knowing that imperfection was okay (and, let’s be real, expected in the hospital) and not to punish myself on busy shifts.

They knew I wanted to do my very best, and they helped me be realistic about that.

Team Morale

Keep it strength-based. The human default is to criticise ourselves and then project that onto others (silly brains). If you think that most people are probably walking around, mentally beating themselves up for their ‘inadequacies’, doesn’t that tell us the value of genuine positive feedback or just a tiny compliment?

I can’t even count the times I’ve assumed a person doesn’t like me, my work isn’t good enough, etc., until I hear positive feedback from a third party. It’s a shame that this kind of feedback isn’t given directly to the person.

I’ve made it my mission to give people positive feedback every day, whether it’s complimenting a stranger on their cool outfit or showing my appreciation to people who have helped and supported me. I’ll always endeavour to formalise positive feedback for good customer service. It’s as valuable or even more valuable than giving a tip. Avoid being disingenuous, but if you can see your team doing good things, no matter how small it seems, say it to them and keep saying it.

If you want to take it to an even stronger level, just validate how your staff feel while reminding them what they are accountable for. Through being a Dialectical Behavioural Therapist, I've learned the effectiveness (and evidence base) behind keeping people accountable (which is empowering to them) while being their cheerleader. Validating how a person feels does not necessarily mean you can fix their problems; it might not even mean that you agree with them, but it reminds them that their feelings are valid. If in doubt, listen and validate.

Strong Leadership

Leadership is modelled well when the leader shows they are a part of the team. The amazing CNC I mentioned earlier on the busy medical ward I worked on would help during the medication round (the busiest part of the shift) and then go on to do her other management duties.

It would not have been realistic for the CNC to be there helping us on the floor for the whole shift; it would have failed all of us if she had done so because she needed to do her tasks that we could not do.

I appreciated it when she expressed limitations on what she could do in certain situations but never made anyone feel they could not approach her. Our CNC's presence made a huge difference for all of us, and we all wanted to go the extra mile for her because she did for us.

Leaders should not be tucked away in offices all day and then send emails to staff highlighting what they are not doing enough.

Great leaders stand there alongside their team, talking to and helping them where possible.

Mental Health Awareness

Please lead by example with this. Do not say to staff, ‘Look after your mental health,’ and then leave the conversation at that. Think about how you can support staff with their mental health on shift. Encourage your staff to have their lunch break and leave on time. If they are not doing that, check in with them and see what is preventing them from doing so.

I would discourage telling staff they need to be more efficient with their time straight off the bat, as there will be a more significant reason why they aren't taking breaks or finishing on time that requires some supportive discussions, i.e., stress, unrelenting standards, or feeling they are letting people down.

Mental health awareness is nothing too outlandish: Keep checking in with your staff, not just about their KPIs but also about their general well-being.

Fair Workload Distribution

In a few workplaces, junior staff are taking on mentorship roles for new staff while senior staff, who are getting paid twice as much, are scrolling eBay to see what next pair of party shoes they will buy. Senior staff need to be able to demonstrate why they are leaders.

Unfortunately, the ‘yes people’ (typically early career nurses with exuding amounts of enthusiasm and goodwill pumping through their veins) are the people who get asked to do more, and they will find it hard to say no.

Some of the ‘no people’ need to do more, but their attitude deters management from asking them to step up to their role.

I feel that for managers, in this sense, an increase in pay packets is necessary to deal with these kinds of situations. Maybe some of the ‘no people’ need to take a holiday or move on to another role, but let's ensure that the ‘yes people’ (the early career health care staff) last more than a year before they resign.

Sufficient Leave

Again, another area where the manager's pay packet is justified is balancing out every person's annual individual requests. This is especially hard when you manage a small team, and everyone wants Christmas off. However, straight-up disparities in managing staff leave will leave them disgruntled.

It can’t be a coincidence that I was rostered on for every single weekend when I was a Nurse in one particular workplace.

At the same time, the shift manager did as few weekends, evening shifts and night shifts as possible to push her over the line to get her 7 weeks of annual leave while she was essentially not doing shift work. All you can do as a manager is be transparent about what limitations you can offer and have a clear system of managing leave requests so that it’s fair for all staff.

If you want to upskill your staff, they will need study leave. If you wish your staff not to burnout and continue to develop resilience, don’t quiz them on their sick leave (also, you are setting up a potential discrimination case).

Open Communication

Several years ago, I was privileged to be interviewed by my mentor (now Dr Jane Douglas) when she was writing her PhD:

Early Career Registered Nurses: How and Why Do They Stay?

Exploring their disorienting dilemmas

I spoke with Jane about making a medication error during my first placement in critical care as a new graduate nurse. I never felt supported in that workplace. I felt like I was always being tested; I was nervous as hell, and as a background, I was the only person in my high school year who was at the top level of English and Science and the bottom level of maths.

Long story short, I made a serious drug error. I felt like a complete failure and like I shouldn’t be a nurse. Maybe that drug error was always going to happen, and of course, it needed to be taken seriously, but how management handled it was terrible.

I also feel confident that if I felt supported in that workplace, I probably would have asked for help. I spoke with Jane about this, crying as I told the story, feeling myself go hot and sweaty because I was waiting for Jane to say something or do something to make me feel worthless because that’s how I was made to feel at the time of the drug error.

I also talked with Jane about my second rotation as a new graduate nurse on the medical ward (the same one with the glowing CNC and clinical facilitator); I was nurtured at this point. I had the clinical facilitator approach me.

She said,’ Rasa, I know what happened. She added, ‘I can see you are a great Nurse; you just need more support.’

That indeed ensued; the clinical facilitator shadowed me in the drug rounds. She knew maths wasn’t my strong point, so she encouraged me to stay focused on the task and not get pulled away with other tasks. She also said that it was okay if I took a bit longer. She encouraged me to study a drug textbook so that I wouldn't just pass my competencies. I would shine with flying colours.

Interestingly, the work on the medical ward was backbreaking, and arguably, it was an even busier and more stressful environment than the critical care ward. The difference was the support around me.

And you know what, that clinical rotation and my third one, I didn’t just pass; I exceeded expectations with flying colours.

Regular Check-ins

Team meetings are a great opportunity to discuss everything that needs to be discussed. This will probably include things that are hard to discuss, i.e., things the team has identified as issues. That means that managers and staff are sharing their ideas and concerns together.

Countless studies, including Martin's (2022), highlight that healthcare workers with higher resilience were given regular opportunities to critically reflect on adverse incidents, including those involving patients, where they felt emotionally safe and did not feel that management was giving them punitive messages.

Transparency is still essential, and having regular times to meet is, too. Like any relationship, brewing on what has been stressing you out for six months, not mentioning any of it along the way, and then reading out the list for twenty minutes in one sitting is hard for anyone to process.

Take the opportunity with these meetings to remind you of things your staff needs to hear, like what they are doing well in. It sounds obvious, but it’s incredible how many missed opportunities there are at these moments. It can mean the difference between having staff members walk out of the meeting, feeling motivated to keep working while feeling supported, or the opposite.

Access to Support Programs

It's like the adequate staff thing. It's a lovely idea, but is it realistic? Where does the funding come from for this?

One of my oldest friends, a psychologist, argues that when people say, “That person needs to go to therapy,” it’s often less about therapy itself and more about the relationship between the two individuals. In many cases, an open and honest conversation between them could achieve the same effect.

The Power of Relationships

I’d like to call upon the amazing Dr Jane Douglas (2019) again with her research. Intersubjectivity is a concept rooted in social psychology and philosophy that refers to the shared understanding and subjective experience between individuals.

Douglas (2019), in her PhD, concluded that intersubjective relationships are a way of knowing about self and others by sharing safe spaces where dialogue, critical reflection, and transformation of perspectives can begin to happen.

Early career registered nurses, their relationships with staff and the associated expectations of their work led to disorienting dilemmas, but relationships also helped them move through them. Disorienting dilemmas are inevitable; it is how we learn, but how people approach them impacts the outcome (Dr Jane Douglas, 2019).

By chance, while participating in a podcast about supporting early career health professionals at risk of burnout, I discovered a free nurses and midwifery counselling service for those in the role. I wish a manager had told me about this when I worked at the hospital!

- Nurse & Midwife Support - A 24/7 national support service for nurses & midwives providing access to confidential advice and referral.

- Nurse Midwife Health Program Australia - Peer support counselling for nurses, midwives and students.

On that token, with existing mental health supports, e.g., Employee Assistance Programs (EAP), encourage your staff to access them. Let them access it for an hour monthly in work time as a minimum. It might make you feel nervous about allowing your staff to get an hour off for EAP/clinical supervision, but honestly, if it preserves their mental health and longevity in the role, it’s a small sacrifice to make.

Proactive Mental Health Monitoring

When I worked in a hospital, I appreciated that staff would check in with me when a patient died on my shift. The thing is, though, I’d been working in aged care since I was 16. Deaths were not traumatic for me, but a lot of other things not involving death were. Perhaps because they’re less obvious, no one checked in, and I felt like it must have been a sign that I wasn’t coping if I raised another situation to be emotionally affecting me.

I know now, as an experienced mental health professional, that trauma is in the eye of the beholder. I wish this were explained to me when I started as a nurse. An extended invitation to talk to leadership about these things would have helped, too.

Excessive sick leave, ‘underperforming’, and irritability are some potential signs that a healthcare worker is not coping. Honestly, a lot of ‘mental health monitoring’ involves genuinely and continuously encouraging people to take leave when they need it and to speak to their manager when they are not coping. The ones who don’t say anything can often suffer in silence. So, just a gentle check-in goes a long way. ‘Are You Okay Day’ was made for a reason.

Resilience Training

Errr, what is this? I’ve never heard of such a course. I would argue that workplaces should know they either have or can implement the strategies needed to promote resilience. Regular clinical supervision, otherwise known as mentorship that excludes management input (monthly for one hour at minimum, as a one-on-one arrangement and/or in a group), has a strong evidence base to prevent burnout and promote professional development and resilience.

Your existing staff can undergo a day's training to be a clinical supervisor and then ‘ta-da’! All the financial costs are kept in house-bonus!

But hey, if you see a course that might support your staff, encourage them to attend it. I’ve personally felt that compassion fatigue courses and retreats have been beneficial in further promoting my sense of self and resilience.

Fostering Resilience Begins with Leadership

To finish, I presented at a palliative care conference with another early career nurse many years ago. One of our key messages was:

Let’s not eat our young but nurture them.

Resilience in early career health professionals is essential; importantly, it is fostered by people

in leadership positions so they can succeed. I wrote an article many years ago, reflecting on my new graduate year, and I said:

‘Look after us, junior nurses. We have a lot to offer - and they may be caring for us one day. 13 years later, as a more experienced nurse than I was back then, I'm echoing those words again.

References and Useful Resources

- What is Resilience? University of New South Wales

- Resilience: A Guide to Facing Life’s Challenges, Adversities, and Crises - Katie Hurley (Everyday Health)

- Resilience - What is It? Australian Radiation Protection and Nuclear Safety Agency

- Resilience - Psychology Today

- Resilience: A Definition in Context - Julie Ann Pooley and Lynne Cohen (Edith Cowan University)

- What Resilience Means (and Why It Matters) - Kendra Cherry (Very Well Mind)

- Nature vs. Nurture? It’s Both - Victor Katch (Michigan Today)

- How to Build Resilience in Healthcare Professionals - Human Focus

- Validation Skills in Counselling and Psychotherapy - Kocabaş, E and m Üstündağ-Budak, M.

- RUOK Day

- Early Career Registered Nurses: How and Why Do They Stay? Exploring their Disorienting Dilemmas - Dr Jane Douglas

- Self Validation - Dialectical Behavior Therapy

- Reflections of a New Graduate Registered Nurse - Rasa Kabalia

- Resilience Among Health Care Workers While Working During a Pandemic: A systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative studies - Curtin, Richards and Fortune.

Author

Rasa Kabaila

Rasa Kabaila is a Nurse Practitioner specialising in mental health and the founder of Broadleaf HNP Services. Her approach is innovative, holistic, individualised, and evidence-based, with a strong focus on recovery-oriented care. Deeply empathetic and passionate about helping others, Rasa began her healthcare career as a personal care worker at just sixteen.

She has successfully implemented research-backed clinical therapies for optimising the treatment of anxiety and depression, including pet therapy. Beyond her clinical work, Rasa has volunteered on nursing expeditions overseas and completed Ashtanga Yoga training in Mysore, India.

Rasa is also a Conjoint Lecturer with UNSW Rural Medical School and has been an academic tutor for undergraduate nurses and paramedics at the Australian Catholic University and the University of Canberra.

Her first book, Put Some Concrete in Your Breakfast: Tales from Contemporary Nursing, was published by Springer Nature in March 2023 and has since been read by over 17,000 readers. It has also been widely promoted across journals, magazines, and news channels.

For more about Rasa’s work, visit her practice website at Broadleaf HNP Services or explore her book, Put Some Concrete in Your Breakfast: Tales from Contemporary Nursing, featured on ABC News, available on Amazon and Goodreads.