Embedding Trauma-Informed Care into Workforce Capability

People leaders, executives, boards, and L&D teams will be familiar with the strengthened Aged Care Standards, which introduce a trauma-informed, healing-aware approach to care. While this may be new to some, those in acute care will recognise its foundations.

The Royal Commission's enquiry into Aged Care has led to the Government introducing new Aged Care standards, which include providing trauma-informed, healing-aware care (Australian Government, 2025).

Many providers are already preparing their workforce, or you may still be finding your way.

This shift is about more than compliance; it’s about building workforce capability to support your teams and embed a trauma-informed care approach meaningfully into daily operations and the inner workings of your organisation, from top to bottom.

This article supports your professional learning and offers practical strategies for moving beyond policy and truly integrating this vital approach into everyday practice.

Understanding Trauma: The Individual Experience

Trauma is defined by its impact on the individual rather than the event itself (NSW Health, 2022). Beck (2004) explored this concept in a study on mothers' experiences of birth trauma, highlighting that trauma is subjective.

What may seem routine to clinicians can be deeply distressing for individuals or patients.

The study identified four key themes reflecting women's experiences:

- To care for me: Was that too much to ask?

- To communicate with me: Why was this neglected?

- To provide safe care: You betrayed my trust, and I feel powerless.

- The end justifies the means: At whose expense? At what price? (Beck, 2004).

Applying Universal Precautions to Trauma-Informed Care

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) introduced ‘Universal Precautions’ in 1985, primarily in response to the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic (Broussard, Chadi & Kawaji, 2023). These precautions are a standard set of guidelines designed to prevent the transmission of bloodborne pathogens through exposure to blood and other potentially infectious materials.

This includes measures such as appropriate hand hygiene, wearing gloves, and the safe disposal of needles (Broussard, Chadi & Kawaji, 2023). The underlying principle of Universal Precautions is that since we cannot always identify who may be carrying an infection, all human body fluids should be treated as potentially infectious (South Australia Health, 2025).

In the same way, we should approach all people in our care - whether patients, colleagues, family members, or employees - with an assumption of past trauma. Since we cannot always know who has experienced trauma, adopting a trauma-informed approach ensures that we provide care that is sensitive, respectful, and conducive to healing.

When embedded into practice, trauma-informed care creates an environment where healing can be fostered.

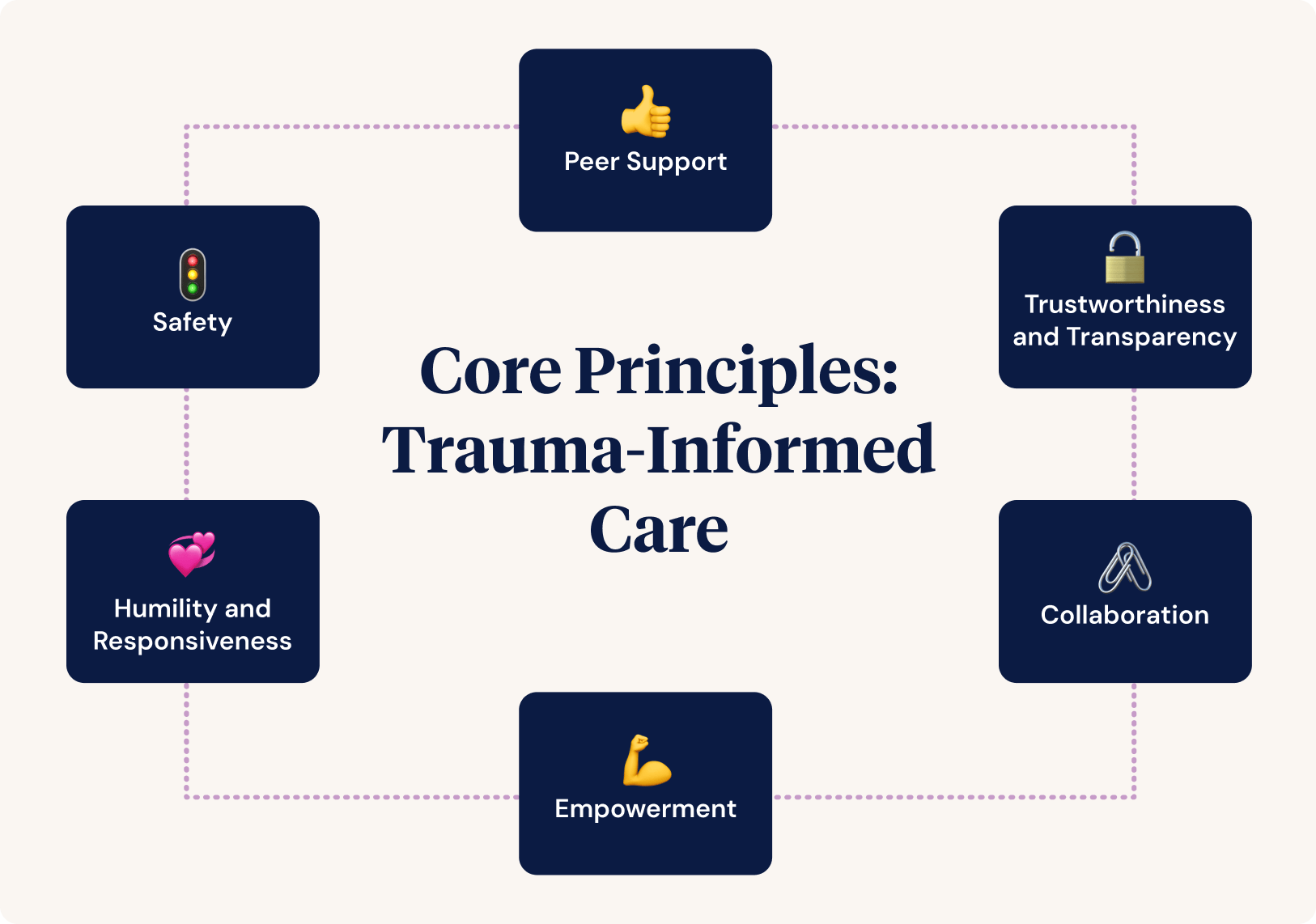

Core Principles of Trauma-Informed Care

The Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Centre (2025) has noted six core principles of trauma-informed care:

- Safety

- Trustworthiness and Transparency

- Peer Support

- Collaboration

- Empowerment

- Humility and Responsiveness

Applying Trauma-Informed Care in Practice

This guide explores the six core principles of trauma-informed care. I started working in Aged Care at 16, and now, as a Nurse Practitioner specialising in mental health, I’ve seen firsthand how these principles can transform care. Anyone who has worked in Aged Care knows that while the role is deeply rewarding, it also comes with significant challenges.

In this guide, I’ll now share how these principles can be applied in practice, keeping in mind the often under-resourced settings where health workers support older people.

- Safety

Throughout the organisation, patients and staff feel physically and psychologically safe.

What this looks like in practice:

- Be conservative when addressing risk, and document and inform management. It’s easy over time to become complacent, and that's where accidents happen.

Think of a carabiner in rock climbing. Carabiners are a reasonably essential yet vital anchor point to assist climbers with clipping their ropes and arresting falls. Rock climbers are safest as beginners because they double-check all the carabiners (routine safety practice). It’s experienced climbers who tend to stop checking each other's carabiners.

The same applies to people driving. New drivers are some of the safest on the road for the first couple of weeks until they gain confidence and become far less safe. Health professionals are no different; it’s easy for something deviant to become your norm. Go back to the foundations of what you were taught at the start about safety.

- Active listening Active listening recognises that sometimes, you don’t need to solve problems; people just want to be heard.

- Ask more questions to clarify what you think you have understood, and paraphrase what you understand about the information you have received.

- Validating how someone feels means letting the person know verbally and nonverbally that their feelings are valid. Validation does not mean you necessarily agree with the person or even understand.

- Trustworthiness and Transparency

Decisions are made with transparency and to build and maintain trust.

What this looks like in practice:

- Management must actively support staff in working through adverse incidents and challenges. Errors are inevitable, especially in busy environments. Encouraging transparency and avoiding a punitive reaction is key to creating a positive culture where people can discuss what has not been planned.

- It’s hard for healthcare workers to want to be transparent about mistakes with clients when they are afraid of legal ramifications. However, when people are not transparent about mistakes, trust is lost.

- Open disclosure should be enacted from the outset. Clearly explain the disclosure process to new staff and clients, reinforcing that honesty builds stronger relationships and trust. People appreciate honesty.

- Peer Support

Individuals with shared experiences are integrated into the organisation and recognised as essential to service delivery.

What this looks like in practice:

The value of peer workers cannot be understated.

- Educational presentations from people who have cared for an elderly partner or family member provide valuable learning opportunities for support staff.

- Many people, particularly older clients, need companionship. However, support workers are often stretched thin with their responsibilities. Consider how your workplace could engage individuals with lived experience as carers to support clients and educate staff.

- Your service clients can have their own committee as a working group in your facility to voice what is important to them and share it with staff. This model is commonly used in psychiatric wards and can be successfully applied in aged care settings as well.

- Collaboration

Power differences between staff and clients and among organisational staff are levelled to support shared decision-making.

What this looks like in practice:

- Think about a time when you were in hospital or seeking support at a vulnerable moment. At these times, you depend entirely on how others communicate with and treat you. You do not hold the power.

- Perhaps you were wheeled off to surgery, crying from fear, while healthcare workers chatted among themselves about their weekend plans. Then, you woke up confused and only partially dressed because someone decided it was easier to leave you that way.

These small moments matter. While this may be just another day at work for you, the person in your care may be scared and vulnerable. Always communicate - even when you think you don’t need to. If you need to leave the room, explain why and give a realistic timeframe for when you will return.

- There should be no ‘them and us’ approach between management, staff, and clients. Everyone deserves to be informed. Regular meetings between all staff and clients to discuss individual goals and care considerations make a significant difference.

- Where possible, be at eye level with the person you support. Those who can extend their posture naturally feel more confident, while those who cannot may feel even smaller.

- Empowerment

Patient and staff strengths are recognised, built on, and validated — this includes a belief in resilience and the ability to heal from trauma.

What this looks like in practice:

- Every person has strengths. Every person wants to feel cared for. Health professionals often waiver from being too distant to being over-involved.

- Strength-based care is not too dissimilar to cheerleading and coaching. We all need support and encouragement to know what we can do.

- A lot of coaching helps people believe in their abilities; they may not recognise themselves, but the coach acknowledges and supports them with what is hard for them.

- The cheerleader is the person waving the pom poms and cheering while being allowed to demonstrate what they are capable of while being witnessed.

- Where are we without hope? When people experience trauma, they need that experience to be acknowledged, but they also need someone to hold a beacon for them when they cannot do it themselves.

- These two things - acknowledging trauma while making space for genuine hope must coexist. This balance is what fosters resilience.

- Humility and Responsiveness

Biases and stereotypes (e.g., based on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, geography) and historical trauma are recognised and addressed.

What this looks like in practice:

- There will always be people you find more challenging to care for or work with for various reasons. Everyone carries biases, judgments, and triggers shaped by their experiences, values, and upbringing. The key is to recognise and acknowledge these without allowing them to interfere with the provision of quality care. Simply admitting your triggers to yourself or a trusted person can help prevent them from affecting your interactions.

- Remind yourself that every person deserves compassion. Whether you agree with their actions or life choices, upholding this principle as a healthcare worker, colleague, or manager is essential.

- Sometimes, you may need to dig deep to find compassion. A useful approach is to ask why—why is this person behaving this way? What experiences might have shaped their emotions or actions?

Put simply, ask - not what’s wrong with this person but what’s happened to this person.

Recognising that people are complex and that we may never fully understand their past or decisions helps maintain professional boundaries. Our clients are not our friends, family, or partners; we do not need to understand their behaviour fully. What matters is that we continue to provide care with professionalism and kindness.

Sustaining Trauma-Informed Care in Practice

If you feel like taking the steps listed above requires a lot of energy, you are correct in your thinking. If you are finding it hard as a healthcare worker to be able to provide trauma-informed care because you feel depleted, then you will need to tap into how you can refill your tank.

For example, this might include debriefing with trusted people, taking a holiday, catching up on sleep, going on some long walks or re-evaluating the work hours that are best for you. Self-care is different for each individual. It’s also not a stagnant one-off thing; it’s a continuous journey.

It’s also essential to recognise that these recommendations (the core principles of trauma-informed care) can only be truly effective if management supports their staff. Workers who do not feel supported are far less likely to raise concerns or seek help when needed.

While it’s encouraging to see the Government taking a more active role in supporting aged care after years of relative inaction, meaningful change will require continued financial and practical investment. Hopefully, further steps will be taken to ensure that those at the forefront of delivering care are properly resourced.

However, regardless of available resources, health workers can make a difference in every small moment. Never underestimate the power of simple, mindful actions, like clearly communicating each step when assisting someone in showering or validating their feelings when they are distressed. By assuming that every individual may have experienced trauma, we can be more intentional in our approach, fostering environments that truly support healing.

References and Useful Resources

- Australian Government - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Aged Care Programs and Reforms

- What is Trauma-Informed Care? - Trauma-Informed Care Implementation Resource Center by the Center for Healthcare

- What is Trauma-Informed Care? - NSW Health

- Birth Trauma: In the Eye of the Beholder - Cheryl Tatano Beck

- Universal Precautions - Broussard and Kahwaji

- Handling Blood and Other Body Substances - SA Health